The Programs (cont'd.)

Candib, whom Dick Walton describes as, "a feisty, confident, verbal, liberated feminist - bright, talented and forceful," joined the program after having completed an internship at Cambridge Hospital. She was based at the FHSSC and went on to become the first woman resident in the program and, after graduating in 1976, the first woman on the faculty. In 1980, she became Medical Director at the FHSSC, although after the birth of her first child, she began to practice part time to allow time for her writing, teaching, and mothering.

Candib, in other words, was not only someone whose political commitments to the underserved predated and, indeed, predisposed her

choice of the Worcester program.

She was also one of the earliest doctors at the health center (or in the Department) to forcefully express a commitment to feminism at a

time when nationally and locally the

Candib, in other words, was not only someone whose political commitments to the underserved predated and, indeed, predisposed her

choice of the Worcester program.

She was also one of the earliest doctors at the health center (or in the Department) to forcefully express a commitment to feminism at a

time when nationally and locally the

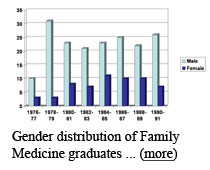

representation of women among residents and medical students was less than 24 per cent. (In fact,

only 11.6 per cent of all practicing physicians in 1980 were women.) Candib herself looks back at those years with a certain measure of

regret,

representation of women among residents and medical students was less than 24 per cent. (In fact,

only 11.6 per cent of all practicing physicians in 1980 were women.) Candib herself looks back at those years with a certain measure of

regret,

however, for initially failing to appreciate the different adaptation styles, scheduling needs and multiple priorities held by residents

who were committed to family practice but also were committed to parenting, especially (back then), women. It took her about a decade,

first as a resident, then as a member of the faculty and the medical director of the Center, and then as a parent-faculty member, to

apply a feminist understanding of the arbitrary nature of gender norms to the organizational structure of family practice.(72)

however, for initially failing to appreciate the different adaptation styles, scheduling needs and multiple priorities held by residents

who were committed to family practice but also were committed to parenting, especially (back then), women. It took her about a decade,

first as a resident, then as a member of the faculty and the medical director of the Center, and then as a parent-faculty member, to

apply a feminist understanding of the arbitrary nature of gender norms to the organizational structure of family practice.(72)

Although Candib attended Harvard Medical School during the last years of the anti-Viet Nam War movement, which she supported, her attention migrated to the politics of social justice here in the United States. Specifically, her activism began to focus on a set of interrelated issues: women's liberation, social inequality in health care, sexism in medicine, and the problem of domestic violence. During medical school she was active in the Boston branch of Bread and Roses, helped launch a free women's health clinic in a blue collar suburb, Somerville, and wrote a chapter titled "Women, Medicine, and Capitalism" for the first edition of Our Bodies Ourselves.(73) Dan Doyle, who was in medical school with Candib, is one of many at the FHSSC who acknowledged Candib's importance as a political role model. He told us,

From working with community groups and just from our own personal beliefs, we didn't like the extreme social distance between the doctor and the patient. And I think we knew that some of it was structural and just had to be. We were not into making it more; we were into trying to make it less. And that also came out in our relationships with other staff members at the health center. We both, and I should mainly speak for myself, but I felt supported by her in this, so we thought that our relationships with the nurses and the ward clerks and people like that, we didn't see them as beneath us. We saw them as partners, we saw them as people we worked with, and who often knew important things about the patients that we didn't, and people without whom we couldn't do our job.(74)

As Candib put it,

It was clear to me that the government and what we called the military-industrial complex—I think we didn't really understand about 'big pharma' then, but I think it would have been pretty obvious if we knew about it—really were out to make money off the backs of people who were very poor and who didn't have a clue what was happening to them. And that health care wasn't any different from that—that the wealthy got better, more informed health care and low-income people and poor people and black people and immigrant people got crummy health care.

In her writings as well as in conversation, Candib's stories of doctoring almost always refer to her patients—most of whom are women and children—in terms of their connection to their families and community. But also, she takes care to relate to them as one individual to another. At the FHSSC Candib and all other health care providers had an opportunity to care for underserved patients as individuals and as a part of large extended families.(75)

In 1974, FHSSC affiliated with the new UMMS Family Medicine Residency as a teaching site. Worcester City Hospital, the residency's hub, was located a short distance from the Center and was tied closely to it both by geographic proximity and because UMass residents played an increasingly important part of City Hospital's workforce, as we will see below in Section 3. And ultimately, when Worcester's city government could no longer afford the expense of maintaining it at the level necessary for accreditation and City Hospital was forced to close, it was the FHSSC that stepped into that breach and supplied the ambulatory health care for thousands of Worcester's urban poor.

Hahnemann Family Health Center

The Hahnemann Family Health Center, the third spoke on Dick Walton's umbrella-model residency program, opened in 1975 at 39 Dean

Street, formerly a college fraternity house across the street from Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI). Like the program at

Fitchburg, the practice itself originated in the office of a private practitioner, in this case, the home-office of the late Dr.

Gerry Commons. Commons worked out of his house in a ground

The Hahnemann Family Health Center, the third spoke on Dick Walton's umbrella-model residency program, opened in 1975 at 39 Dean

Street, formerly a college fraternity house across the street from Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI). Like the program at

Fitchburg, the practice itself originated in the office of a private practitioner, in this case, the home-office of the late Dr.

Gerry Commons. Commons worked out of his house in a ground

floor office and helped remodel the former WPI fraternity house on the

same block into the new site. In Dick Walton's words, "Gerry Commons, a highly respected, wonderful family physician [who] practiced

out of the first floor of his home and had taken our med students, became the biggest pioneer of all when he took his life's

practice and his work and brought it all to Dean Street." Commons was considered an epitome of dedication, although not

necessarily a model of, in today's jargon, "work-life balance." Len Finn described Commons's practice style this way:

floor office and helped remodel the former WPI fraternity house on the

same block into the new site. In Dick Walton's words, "Gerry Commons, a highly respected, wonderful family physician [who] practiced

out of the first floor of his home and had taken our med students, became the biggest pioneer of all when he took his life's

practice and his work and brought it all to Dean Street." Commons was considered an epitome of dedication, although not

necessarily a model of, in today's jargon, "work-life balance." Len Finn described Commons's practice style this way:

We ought to talk about Gerry Commons [who] had the exact same reputation that Bob Babineau had, in that he was beloved by his patients, he was a wonderful comprehensive family doctor, a great communicator, a nice person to be with. The big difference between him and Bob Babineau was that he was never on time. He sat and listened to each patient until they were finished and he listened to everything they had to say, addressed every problem. And the patients knew that this was going to be the experience, and they brought their books or their sewing or their knitting or the newspaper and sat in the waiting room and just waited. His waiting room was in his home, his office was in his home. He might grab a quick bite at suppertime and continue seeing patients until 8 or 10 in the evening, until everybody had been seen.(76)