The Programs (cont'd.)

Just as important, Walton and Pickens formed strong connections to the administrations of the community hospitals with whom they hoped to cement working ties for the residents. As the residency took hold, by 1976 they were carrying out patient care on a newly designated Family Medicine floor at Holden Hospital as well as doing Obstetrics at St. Vincent's Hospital. Once Holden Hospital had closed in 1990 (after a brief clinical partnership with Hahnemann and Memorial hospitals), the residents and faculty were assigned an explicitly designated floor for Family Medicine at Memorial. Medical students began doing rotations at Barre in the late 1970s, and by 1980 it was clear the Center would have to move or expand. In 1984 a new Center was opened on Worcester Road, and after a "modest expansion" in 1996, it remained there until a new, larger building was opened in 2007.

The Family Health and Social Service Center of Worcester

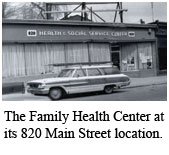

The Family Health Center in downtown Worcester was established in 1970 as part of the Great Society Model Cities program and,

until the founding of the Worcester residency program, was entirely independent of the medical school. If the Barre program

exemplified rural and small-town health care, the downtown site was its sociological antithesis. Originally located in a storefront

on a worn-down-looking block of Main Street, the Family Health Center had the look and feel of front-line, urban health care. In

1972, it incorporated as the Family Health and Social Service Center of Worcester (FHSSC), an acknowledgement of its multifaceted

role in serving the residents of one of Worcester's oldest—and poorest—neighborhoods, known locally as "Main South." In

September

The Family Health Center in downtown Worcester was established in 1970 as part of the Great Society Model Cities program and,

until the founding of the Worcester residency program, was entirely independent of the medical school. If the Barre program

exemplified rural and small-town health care, the downtown site was its sociological antithesis. Originally located in a storefront

on a worn-down-looking block of Main Street, the Family Health Center had the look and feel of front-line, urban health care. In

1972, it incorporated as the Family Health and Social Service Center of Worcester (FHSSC), an acknowledgement of its multifaceted

role in serving the residents of one of Worcester's oldest—and poorest—neighborhoods, known locally as "Main South." In

September

1973 the Center bought a former secretarial school at 875 Main Street (a building purposely constructed without windows, according

to local lore, to avoid

distracting secretarial students from their touch-typing and dictation instruction), and remodeled it to

accommodate its dual mission as a family practice and a neighborhood social service hub. (It was renamed the "Family Health

Center-Worcester" in 1999.)

1973 the Center bought a former secretarial school at 875 Main Street (a building purposely constructed without windows, according

to local lore, to avoid

distracting secretarial students from their touch-typing and dictation instruction), and remodeled it to

accommodate its dual mission as a family practice and a neighborhood social service hub. (It was renamed the "Family Health

Center-Worcester" in 1999.)

The neighborhood, originally home to first-generation Jewish, Polish, and Italian immigrants in the late nineteenth century, became

in the 1960s and 1970s a "migration destination" for Puerto Ricans, some of whom had only recently emigrated from the rural villages

where their families had lived for generations. Some had arrived only after previous attempts to settle in New York or other

northeastern cities.(65) These new Worcester residents had come in search

of jobs, usually finding one of many

service jobs which were filling the employment void created by the closure of large-scale manufacturing all across the Northeast.

More recently, the cycle has been replicated by migrants from Africa, Central and South America, and Southeast Asia. The

neighborhood also included a population of African Americans, but in the 1970s they were a smaller component than

Hispanics.(66)

in the 1960s and 1970s a "migration destination" for Puerto Ricans, some of whom had only recently emigrated from the rural villages

where their families had lived for generations. Some had arrived only after previous attempts to settle in New York or other

northeastern cities.(65) These new Worcester residents had come in search

of jobs, usually finding one of many

service jobs which were filling the employment void created by the closure of large-scale manufacturing all across the Northeast.

More recently, the cycle has been replicated by migrants from Africa, Central and South America, and Southeast Asia. The

neighborhood also included a population of African Americans, but in the 1970s they were a smaller component than

Hispanics.(66)

Melvin Pinn, who graduated from the FHSSC site in 1979, described it this way:

It was an interesting place, it was very crowded, it was very packed, the waiting room was always filled, and there was a mixture of conversations all the time of Hispanic people, all kinds of people sitting in the waiting room, just a hustle and a bustle … I just think that we had what would probably be in today's terms a normal waiting room, people with their individual problems looking to get help, and befriending the people that were sitting beside them. So I thought it was a pretty calm atmosphere, actually.(67)

Melissa Greenspan, remembered her impressions of the FHSSC from her initial residency interview (her home base turned out to be Hahnemann):

My first interview was with John Frey, and I really liked John. I felt very comfortable with him. I really liked his idea about what the residency was going to be about. I went out to what was called Main Street then, [now] Family Health and Social Service Center, and talked fairly briefly I think with Lenny Finn. It was pretty chaotic there. I wasn't real impressed. I remember that the space that the residents were writing their charts in and stuff was extremely cramped, with people breathing down each others' neck, but I liked what I knew about Main Street in that it was serving an underserved community.(68)

All in all, the Main South neighborhood presented a set of multiple challenges for health care providers. As Roger Bibace framed

All in all, the Main South neighborhood presented a set of multiple challenges for health care providers. As Roger Bibace framed

the situation, Main South was "a first settlement area. That's when immigrants first come to an area, they settle in an area that's

relatively poor and the rents are low, and this was an area like that."(69) Neighborhood residents required much

more than health care narrowly defined; rather, they needed assistance with language skills, education, unemployment and welfare

bureaucracies, food stamps, legal aid, and mental health care. But the challenges were also part of the attraction for some of the

earliest residents and faculty. As Dr. Lucy Candib has written, "In those years, family practice … appealed to dissidents,

mavericks, and generalists at heart … It was critical of established medicine for dividing patients into body parts, according

to specialty. It focused on the doctor-patient relationship. It

encouraged taking care of children and their parents, not children

the situation, Main South was "a first settlement area. That's when immigrants first come to an area, they settle in an area that's

relatively poor and the rents are low, and this was an area like that."(69) Neighborhood residents required much

more than health care narrowly defined; rather, they needed assistance with language skills, education, unemployment and welfare

bureaucracies, food stamps, legal aid, and mental health care. But the challenges were also part of the attraction for some of the

earliest residents and faculty. As Dr. Lucy Candib has written, "In those years, family practice … appealed to dissidents,

mavericks, and generalists at heart … It was critical of established medicine for dividing patients into body parts, according

to specialty. It focused on the doctor-patient relationship. It

encouraged taking care of children and their parents, not children

in opposition to their parents. It emphasized a low-technology, whole-person, whole-family approach."(70) Two of the

program's 1977 graduates, Dan Doyle and June Tunstall, although trained at the urban Family Health and Social Service Center, chose

in opposition to their parents. It emphasized a low-technology, whole-person, whole-family approach."(70) Two of the

program's 1977 graduates, Dan Doyle and June Tunstall, although trained at the urban Family Health and Social Service Center, chose

to practice in the rural counties of Appalachia; each one was honored with grants from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's Rural

Practice Project in 1978 and 1979, respectively.(71) Doyle traveled to Scarboro, West Virginia to open

the New River Family Health Center, while Tunstall, the first African American resident in the Worcester program, opened the Surry County Family

Health Group in Virginia, her home state. Both have devoted themselves to the care of the rural poor ever since then.

to practice in the rural counties of Appalachia; each one was honored with grants from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's Rural

Practice Project in 1978 and 1979, respectively.(71) Doyle traveled to Scarboro, West Virginia to open

the New River Family Health Center, while Tunstall, the first African American resident in the Worcester program, opened the Surry County Family

Health Group in Virginia, her home state. Both have devoted themselves to the care of the rural poor ever since then.